Search us!

Search The Word Detective and our family of websites:

This is the easiest way to find a column on a particular word or phrase.

To search for a specific phrase, put it between quotation marks. (note: JavaScript must be turned on in your browser to view results.)

Ask a Question! Puzzled by Posh?

Confounded by Cattycorner?

Baffled by Balderdash?

Flummoxed by Flabbergast?

Perplexed by Pandemonium?

Nonplussed by... Nonplussed?

Annoyed by Alliteration?

Don't be shy!

Send in your question!

Columns from 1995 to 2006 are slowly being added to the above archives. For the moment, they can best be found by using the Search box at the top of this column.

If you would like to be notified when each monthly update is posted here, sign up for our free email notification list.

If you would like to be notified when each monthly update is posted here, sign up for our free email notification list.

Trivia

All contents herein (except the illustrations, which are in the public domain) are Copyright © 1995-2020 Evan Morris & Kathy Wollard. Reproduction without written permission is prohibited, with the exception that teachers in public schools may duplicate and distribute the material here for classroom use.

Any typos found are yours to keep.

And remember, kids,

Semper Ubi Sub Ubi

|

Head to toe woe.

Dear Word Detective: I recently was told that I was “besmirching” a friend of mine. When I asked the speaker if he knew what that meant, he said, “No, but, you said it last week and I thought it meant ‘bad’.” I told him that’s pretty much it. Now I am going crazy trying to figure out what a “smirch” is. Please help. — Anthony Jolley.

That’s a good question, and it’s nice to hear that folks out there are debating the meaning, and puzzling over the derivation, of words. Eventually, of course, many of you end up here, so in a sense I guess I’m doing technical support for the English language, just like those nice folks you call when your Dell plays dead. The difference is that I won’t be asking you to reformat your brain and reinstall English 101 unless it’s absolutely necessary. Please hold.

OK, so we have a problem with “besmirch.” That’s a shame, because “besmirch” is one of our most tested and reliable words, having been employed in the English language for more than four centuries. The first recorded use of “besmirch” in print, in fact, was in Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” in 1602, although he used an early version of the word and spelled it, along with a lot of other things, rather strangely (“And now no soyle nor cautell doth besmerch the vertue of his feare”).

Today we use “besmirch” to mean “sully” or “tarnish,” most often in a figurative sense, and almost always in the idiom “to besmirch someone’s reputation,” meaning to damage their public image or popularity. In a literal sense, however, “to besmirch” means to soil or discolor with mud, soot or other dirt. But this literal use is extremely rare, and I can’t imagine it being used as anything but a mock affectation (“I say, Madame, your dreadful little dog has besmirched my new boots”).

You ask what a “smirch” might be, and there is indeed a noun “smirch” meaning “a smudge, stain or dirty mark” (and, figuratively, “a moral stain or flaw”). But that noun, which appeared around 1688, is more recent than the verb “besmirch.” More importantly, it is far younger than the verb “to smirch” (no “be”), which appeared way back in 1495 and which gave us both the verb “to besmirch” and the noun form “smirch.” This verb “to smirch,” which lies at the root of all this tarnishing and sullying, comes from the Old French “esmorcher,” which meant to torture or torment, especially by the application of hot metal objects. The change in sense from “burn” to “dirty” may have had to do with the marks left on the victim by the torture.

So, since we already had “smirch” as a verb meaning essentially the same thing as “besmirch,” where did the “be” come from? “Be” is a very common prefix in English, meaning a variety of different things in different contexts. In the case of “besmirch,” it carries the meaning of “around or all over,” so to “besmirch” someone is not merely to “smirch” them, but to give them a full-body “smirching.”

Polly want a sweater?

Dear Word Detective: I am trying to find a definitive answer for my 7th grade health students on the popular term “cold turkey.” How did quitting an addictive substance suddenly, without any help, lead to this phrase? — Mrs. McRae’s 2nd period health class.

Oh boy, health class. We didn’t have health class when I went to school, which probably explains a lot of my subsequent behavior. We did have shop class, where I learned how to perforate myself with a drill press and developed a lifelong fear of power tools. And we had gym class, where I learned how to climb a rope suspended from the ceiling, a skill that I was, at age 12, convinced would serve me well in later life. I’m still waiting. Unfortunately, life has turned out to be a lot more like dodgeball than rope-climbing.

“Cold turkey” is, as you say, a slang term for suddenly quitting an addictive substance (or, by extension, any habit or pattern of behavior), with no tapering off or substitution of a milder alternative. Although the phrase is today part of the general public lexicon and is applied to even minor inconveniences (“My Blackberry died, so I went cold turkey all afternoon”), “cold turkey” was originally a term known only to the underworld of hard drug addicts and those, such as the police, who had regular contact with them.

“Cold turkey” first appeared in print (as far as we know) in the 1920s, but since such terms are often in use for years or decades before a journalist notes them, it may actually be much older. Interestingly, “cold turkey,” as used among addicts hooked on heroin, morphine or similar drugs, referred to more than just the act of quitting suddenly. “Cold turkey” also meant the often extremely painful physical and mental symptoms of sudden and complete withdrawal from the drugs, “withdrawal sickness” so severe that it could actually cause death.

The origin of “cold turkey” is not entirely certain, but the phrase seems to have evolved from the older (19th century) classic American idiom “to talk turkey,” meaning “to speak directly and frankly, without beating around the bush.” There are a number of stories about the origin of “talk turkey,” many of which involve Pilgrims and Indians, and all of which strike me as deeply implausible. But, more importantly for our purposes, an early form of the phrase was “to talk cold turkey,” most likely using “cold turkey,” a simple, uncomplicated meal, as a metaphor for simple, unadorned, direct speech. With “talk cold turkey” already a popular idiom meaning “give it to me straight; tell me the unvarnished truth,” it seems natural that “cold turkey” came to mean “quit suddenly, with no tapering off or equivocation.”

Not my job.

Dear Word Detective: My sister and I have a bet regarding the phrase “passing the buck.” I think it refers to the early 19th century Kansas frontiers when it was common to pass around large plates of venison. She insists that the phrase originated when the term “greenbacks” was shortened to “backs” and then “bucks,” which makes even less sense. We clearly need your help. — Daniel Jorgenson.

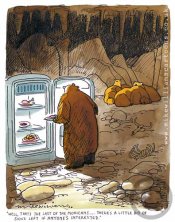

Large plates of venison? I’ll pass, thanks (and yes, I’ve tried venison, many years ago). For some reason, that theory reminds me of a Mike Williams cartoon from Punch we used to have taped to our refrigerator, which showed a bunch of bears lounging around in their cave. One is peering into the refrigerator and saying, “Well, that’s the last of the Mohicans … there’s a little bit of Sioux if anyone’s interested.” (Cartoonist’s website is here.) Large plates of venison? I’ll pass, thanks (and yes, I’ve tried venison, many years ago). For some reason, that theory reminds me of a Mike Williams cartoon from Punch we used to have taped to our refrigerator, which showed a bunch of bears lounging around in their cave. One is peering into the refrigerator and saying, “Well, that’s the last of the Mohicans … there’s a little bit of Sioux if anyone’s interested.” (Cartoonist’s website is here.)

To “pass the buck” today means to evade responsibility by shifting it to another person. The term comes from the game of poker as played in 19th century America, where players took turns acting as dealer. To keep track, a marker known as the “buck,” often a knife with a handle made of buck horn, was placed on the table in front of the dealer, and passed to the next player before each round (“I reckon I can’t call that hand. Ante and pass the buck,” Mark Twain, 1872). By the early 20th century, “pass the buck” had spread from meaning “to transfer responsibility from one poker player to another” to meaning “to shift responsibility for anything to another person,” the sense we use today.

Although “buck passing” is a core survival skill for anyone working in a large organization (especially a government bureaucracy), being on the receiving end of “Oh no, you need to talk to the Office of Non-Euclidean Contingencies, Room 647 in Building B-104″ can be very annoying. It’s even more annoying when the bureaucrat saying that is a politician you voted into office. So in 1949, when President Harry Truman put a sign on his Oval Office desk announcing that “The buck stops here,” he meant that he would accept ultimate responsibility for the actions of his government. Whether that promise was kept is, of course, a matter of opinion, but the slogan was an instant hit and “the buck stops here” is still invoked dozens of times in every presidential race.

As for your next question (I’m psychic), why a dollar is known as a “buck,” the answer is uncertain. Some say that it comes from the use of deer hides (“buckskins”) as currency worth one dollar in early America, but buckskins were worth more than that and “buck” meaning “dollar” didn’t become popular until the 20th century. It’s more likely, in my opinion, that “buck” in this sense is derived from the slang “sawbuck,” meaning a ten-dollar bill. The Roman numeral “X” (meaning ten) was emblazoned on early ten-dollar bills, and resembled a “sawbuck” (from the Dutch “zaag-bok”), or what today we call a “sawhorse.” Since a “sawbuck” was worth ten dollars, people may have assumed (especially after the “X” was removed from the bills) that “saw” had something to do with “ten,” so just one dollar must be a “buck.” That’s just my own theory, of course, but I like it.

|

Makes a great gift! Click cover for more.

400+ pages of science questions answered and explained for kids -- and adults!

FROM ALTOIDS TO ZIMA, by Evan Morris

|

can be found

can be found

Large plates of venison? I’ll pass, thanks (and yes, I’ve tried venison, many years ago). For some reason, that theory reminds me of a Mike Williams cartoon from Punch we used to have taped to our refrigerator, which showed a bunch of bears lounging around in their cave. One is peering into the refrigerator and saying, “Well, that’s the last of the Mohicans … there’s a little bit of Sioux if anyone’s interested.” (Cartoonist’s website is

Large plates of venison? I’ll pass, thanks (and yes, I’ve tried venison, many years ago). For some reason, that theory reminds me of a Mike Williams cartoon from Punch we used to have taped to our refrigerator, which showed a bunch of bears lounging around in their cave. One is peering into the refrigerator and saying, “Well, that’s the last of the Mohicans … there’s a little bit of Sioux if anyone’s interested.” (Cartoonist’s website is

Recent Comments